A Conversation with Historian Ronald Coleman on Reporting Utah’s Black History

Join United Way of Salt Lake as we engage in a series of conversations with some of the inspiring Black Utahns committed to making a difference in our state.

It can be easy to think of history as “stuff that happened.” It’s just the past — a list of people and events going back further and further in time. If you want to know about key dates or notable events, you do a Google search or open a history book, and just like that you have the answer.

However, history is far from that simple. It’s something that is deliberately, painstakingly reported on a daily basis. The historians who do this, the gatekeepers of our past, come with their own human experiences and the biases that includes. The result is a product that might look pretty close to the truth, but will undoubtedly be missing certain people, events, or motives. The more unique perspective and backgrounds that come together to build history, the more these gaps are filled in.

These unintentional omissions played a crucial role when Ronald Coleman was working on his master’s degree in 1972. He was studying at California State University in Sacramento when an advisor (the late Frank Kofsky, a historian well-known for his writing on both politics and music) recommended he focus on Black history in Utah, where Coleman had lived while earning his bachelor’s degree and playing football for the University of Utah.

“I told him that topic had already been studied,” Coleman recalled telling Kofsky. “To which he told me, ‘Not from a Black perspective.’”

That got things in motion. Soon after completing his master’s degree, Coleman headed back to the University of Utah to work on his doctorate degree in history, where he wrote his thesis: A History of Blacks in Utah, 1825-1910. Coleman chronicled nearly 100 years, starting with Black fur traders, then slaves who arrived in Utah with the earliest Latter-day Saint settlers, and ending with the political division growing in the Black community during the early 20th century.

Coleman’s sources for research were numerous — the mark of a good historian, of course. He made connections at the university library in the Special Collections, the LDS Church History Department, and with the descendants of the very people he was researching and writing about. It was here that Coleman got to know one of his favorite people he would encounter while documenting Utah’s history: Mary Lucille Perkins Bankhead.

“She was a no-nonsense, tough woman,” said Coleman. “I simply adored her.”

Bankhead, who passed away in 1994, had an incredibly storied ancestry. Her great grandfather was Green Flake. You can find his name listed under “colored servants” on the Brigham Young Monument in Salt Lake City’s Temple Square. The monument lists every member of the party that arrived in Utah in 1847, including the three Black slaves they brought with them.

Relationships with members of Utah’s historic Black families helped Coleman build a more complete picture of the Black history in Utah. His post-doctoral work focused on historical events and people, including Bankhead’s ancestors and the Black trappers and mountain men who arrived in Utah before 1825.

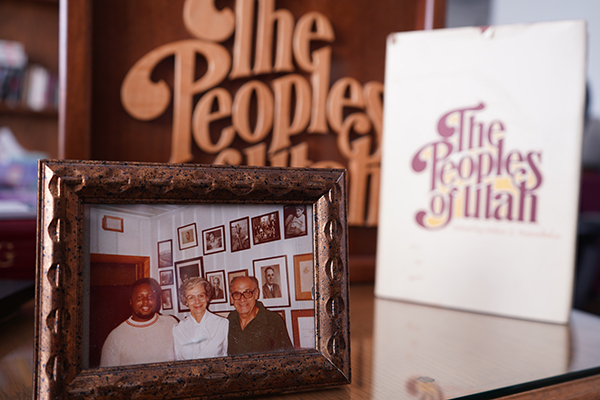

In 1974 Coleman met Helen Papanikolas. Papanikolas was born in Utah to Greek immigrant parents in 1917. Like Coleman, she had an interest in history and studied it at the University of Utah. And like Coleman, she saw gaps in Utah’s history that were left out by most Eurocentric accounts. So, she set out to do something about it.

She sought out others who didn’t fit the majority demographic of the Beehive State and asked them to help her tell the stories of those who slipped through the cracks of many history books. Authors of Native American, Jewish, Chinese, Middle Eastern, and other backgrounds came together to lend their hands in telling a more complete history of Utah. And who, for the section on Black history in Utah, could be better than Coleman?

“I titled it what I felt was the situation here, ‘Blacks in Utah: An Unknown Legacy,’” said Coleman of the text that included people “who had traditionally been left out of the Utah heritage books.”

The Peoples of Utah, with 19 authors listed, was published in 1976. It was a testament not only to Papanikolas’ determination but also to the desire for people to see their heritage rightly written in history. The past is unchangeable, but the work of historians gives us the chance to reflect on how we got to where we are today.

“I’ve been involved with history for a long time, and you go where the evidence takes you,” said Coleman. “Sometimes you might find a clash with your previous perspectives, and if you’re honest you adjust them.”

“Your perspectives, not the history,” he added with a laugh.

Ronald Coleman saw a gap in the story of Utah and decided to act. The rest, as they say, is history.

Get notified of our next addition to the series by following along on our Facebook Page and see our other Black History Month blogs here.

By Grant DeVuyst, Social Media Manager, United Way of Salt Lake