How France Davis Advocated for Change as a Reverend and Teacher

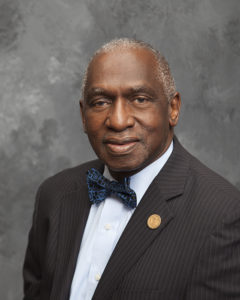

In 1963, Rev. France Davis stood in the audience of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech. Thirty years later, he was a leading advocate for Salt Lake City to name 600 South after the renowned activist. And in 2021, the street in front of Calvary Baptist Church was renamed “Pastor France Davis Way” to recognize Davis’ impact in the fight for racial equity in Salt Lake City.

Davis took the long route from Georgia to Utah. He spent time in Alabama, Texas, Vietnam, Thailand, Idaho, and California, all before making it to the Beehive State. And all before turning 30 years old.

He moved from Georgia Alabama’s historic Tuskegee University, where he began studying agricultural engineering. There, he was involved in the civil rights movement – Davis and many of his classmates met and walked with King on the celebrated march from Selma to Montgomery.

“It was exciting on the one hand, but scary on the other hand,” Davis said. “Exciting in that you could see that we were making some positive changes for the citizens in the community; scary though because we were always worried about the Klan or what people might do to us because we were out marching for change.”

Davis took a temporary pause from school and joined the U.S. Air Force – at the height of the Vietnam War. He picked his education back up at the University of California, Berkeley, where he graduated with a bachelor’s degree.

Then, in 1972, Davis moved to Utah to attend The University of Utah, where he would earn his master’s degree. He also began a teaching fellowship as a graduate student and continued teaching at the university for more than 40 years.

After arriving in Utah for school, Davis found a home in Calvary Baptist Church in Salt Lake City. As a practiced orator and student of rhetoric and communication, he was soon more than an attendant.

“I became a member of the Calvary Baptist Church in 1972, then in ’73 I was the interim pastor and in ’74 they invited me to stay as pastor,” Davis said. “I was pastor at Calvary Baptist Church for 45-plus years.”

More than four decades of leading a church while also teaching at the University of Utah sounds like a full-time job, but it’s only part of what defines Davis’ life’s work. He was an agent for change in the state of Utah.

“Not because I was a pastor, but because of my own experiences,” Davis said on why he chose to be an advocate for systemic change in his community. “I was denied a place to stay, so the first thing I had to do was ensure there was fair housing for everyone in the state of Utah. So that’s what propelled me.”

It was his background in the brutal systemic racism of the South that prepared Davis for what he had to do in Utah.

“I had grown up in Georgia where similar problems existed, and we had been working to resolve some of those and had success solving those problems,” he said. “I would say Utah was essentially twenty to thirty years behind the times, legally. There was no law on the book for fairness and justice.”

To illustrate his claim, Davis told of his experience at Brigham Young University. He was invited to the campus, as a teacher from the University of Utah, but when he showed up was asked to leave the campus due to his hairstyle, an afro.

Davis wasn’t okay with the way things were, so he used his position as a newly minted pastor — a leader of the community — to begin pushing for change.

“First of all, I became a member of the Utah State Board of Corrections and stayed there 10 years,” Davis said. “It was a policy-making board in those days, instead of an advisory board, which it is now. We began to make changes in the corrections system.”

He was appointed to the position by Gov. Calvin L. Rampton, who also saw the need for Utah to move forward. From the board, Davis led the opening of halfway houses to assist the formerly incarcerated and began instating a more diverse staff in the corrections system.

The other main factor Davis prioritized in advancing equity was access to quality education. He wasn’t alone in these efforts. He worked with other Black pastors from the Trinity African Methodist Episcopal Church and New Pilgrim Baptist Church. They saw beyond denominational lines to build a better community for not just their own congregations, but everyone in Utah.

Across various facets of life where people were hurting, Davis, his fellow pastors, and others combined forces to bend the most powerful institutions in Utah toward justice.

“The other problem still exists, and that is: How do we change the attitudes of the common, everyday people? And that, we’re still working on,” he said.

For Davis, changing the opinions of the population begins with meaningful moves from those the people look up to.

“It starts with the leaders not just believing something but putting into practice what they believe,” Davis said.

“For example, the federal government passed the Martin Luther King holiday as the third Monday in January, well Utah was one of the states that said the federal law didn’t apply to them,” he added “So, we had to get a Utah law introduced and passed. To get a street named for Dr. King was even more problematic — we had to get the city as well as the state to cooperate.”

It’s been a long fight for Davis, and even though he’s now retired as a teacher and pastor, he knows there is more to be done. Utahns can be a part of more progress in their communities by advocating for things they believe in.

“Well, the first one is to become a registered voter, and everybody that’s eligible ought to be a registered voter,” Davis said of actions individuals can take for advocacy. “Secondly, more people ought to decide that it’s important to run for offices at every level. We need more people to run for mayor, city council, dog catcher, whatever other positions there are.”

Too young to vote? He has advice for you, too.

“I tell the young people they can become the legs for older people like myself,” Davis said. “I’m not able to do a lot of marching and walking anymore, so the young people have got to do that. I think secondly that they can still write to the legislators and elected officials and remind them that they are a part of this community.”

Learn more about the Black Utahns who have made a difference in our community in our Black History Month series.

By Grant DeVuyst, Social Media Manager with United Way of Salt Lake